In the area of cognitive social abilities, Stephen

Greenspan’s theoretical/conceptual model of personal

competence has been most prominent. Building on the tradition

of Edgar Doll’s (Doll, 1941) definition of mental

retardation, which included “social incompetence” as

one of six criteria, Greenspan (Cunningham, 1997; Greenspan &

Driscoll, 1997; Greenspan & Granfield, 1992) has argued that

the components of personal competence associated with social

awareness or intelligence have been overlooked in definitions of

individuals with mental retardation.

Greenspan’s “Model of Personal

Competence”, first articulated in 1981, emphasizes the need

for individuals working with individuals with disabilities to pay

as much attention to social awareness as is paid to cognitive

abilities (i.e., intelligence) and adaptive behavior. Although

Greenspan’s taxonomy has undergone a number of revisions over

a span of approximately 25 years (including revisions back to prior

models), the basic structure remains a powerful influence on the

work of researchers in the area of social competence and cognitive

social ability. For example, the Greenspan model has played a

prominent role in recent professional and scholarly attempts to

define mental retardation (Conyers et al., 2002; Jacobson &

Mulick, 1996; Schalock & Braddock, 1999; Thompson, McGrew,

& Bruininks, 2002). Although Greenspan’s

conceptualization of social competence, social awareness, and/or

social intelligence has morphed in various directions over the

years, we use his 1985 model of social awareness as the cognitive

dimension of social/interpersonal ability in this paper. A

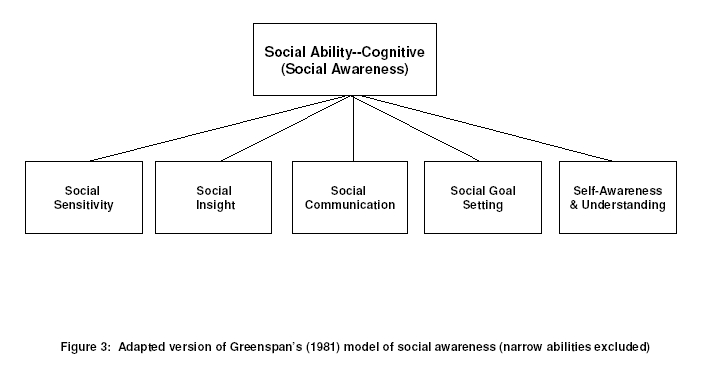

schematic representation of an adapted Greenspan social awareness

model is presented in Figure 3.

“Social awareness [italics added] may be

defined as the individual’s ability to understand people,

social events, and the processes involved in regulating social

events. The emphasis on interpersonal understanding as the

core operation in social awareness indicates that this construct is

a cognitive component of human competence” (Greenspan, 1981a,

p. 18). Greenspan’s social awareness taxonomy is

divided into the 3 broad domains of social sensitivity, social

insight, and social communication.

Greenspan views social sensitivity as a

person’s ability to correctly interpret the meaning of a

social object or event. Subsumed under the umbrella of social

sensitivity are the subdomains of role-taking (ability to

understand the viewpoint and feelings of others) and social

inference (ability to correctly interpret social situations).

Social insight “may be defined as the individual’s

ability to understand the processes underlying social events and to

make evaluative judgments about such events” (Greenspan,

1981a, p. 20). Subsumed under social insight are the narrower

abilities of social comprehension (“ability to understand

social institutions and processes” [Greenspan, 1981a, p.

20]), psychological insight (ability to interpret and understand

one’s personal characteristics and motivations), and moral

judgment (ability to evaluate and make judgments about another

individual’s social actions in relation to moral and ethical

principles). Social communication, the final broad social

awareness domain in Greenspan’s model, is defined as

“the individual’s ability to understand how to

intervene effectively in interpersonal situations and influence

successfully the behaviors of others” (Greenspan, 1981a, p.

21). Components of social communication include referential

communication (ability of an individual to relate his/her feelings,

thoughts, and perceptions to others) and social problem-solving

(ability to understand how to influence the behavior of others in

order to attain a desired outcome).

Greenspan’s taxonomy, which in reality is

more of a working model, provides much needed structure to a domain

(social competence) that has often been marked by confusion and

debate over what social competence encompasses, how best to define

it, and what to call it. Given that the “hardening of

the categories” in the social awareness domains has yet to

occur, we have added, based on the current literature review, an

additional social cognitive ability to the Greenspan model

represented in Figure 3.

Drawing from the previously discussed literature

on social-cognitive models of motivation, social goal-setting has

been identified as an important student characteristic related to

school learning. According to Wentzel, (2002), the day-to-day

experiences of children raise many socially related questions

(e.g., How and why children strive to achieve social

outcomes?, What type of social goal setting

occurs?).

Social goal setting is defined as the setting of

goals to achieve specific social outcomes (e.g., making friends) or

to interact with others in certain ways (e.g., assisting someone

with a task). A major social cognitive challenge for

children, particularly for some children with disabilities, is the

setting of social goals in pursuit of peer acceptance and avoidance

of social conflict (Parkhurst & Asher, 1985). This is a

challenging task given the inherently ill-defined, complex, and

nuanced world of social situations (e.g., classrooms). Research

linking pro-social goal- setting and school success and adjustment

indicates that social goal-setting should be considered as one of

the many MACM domains (Covington, 2000; Wentzel,

2002).